- Home

- Georges Pellerin

The World in 2000 Years Page 2

The World in 2000 Years Read online

Page 2

Whether by virtue of her name, her affections or her opinions, the Marquise was a Legitimist, but not one of those retrograde Legitimists who shine in the Chambre and the Senat by their untimeliness; she was a liberal Legitimist. Understanding and admiring the work of Progress, she knew enough to make the Republic the concession of its interests, but she only admitted the progress sanctioned by divine right in the person of its representative. A sublime Utopia, combining two principles, each of which is the opposite of the other! Extreme, always extreme, the worthy Marquise! In a word, she dreamed of the monarchy restored by Louis XVIII and overturned by the intolerance of Charles X—and, bizarrely, she applauded 1848 because 1848 was the punishment of 1830. She had not forgiven the Orléans monarchy its original task.

In her salon, the Marquise is enthroned in the midst of an animated circle of men and women of all ages, all ranks and all positions. She is 60 years old, although her tall and proud figure, which she hides beneath a dress in the Watteau style, makes her seem younger, and her hair, as white as snow, lifted to the top of her head and falling back in long ringlets on either side of her face, makes her seem older. She has what is required, however, to balance the contrary opinions exactly: a fine and imposing face, slightly wrinkled, a Bourbon nose with a slightly arched profile and blue-gray eyes that the habit of observation has endowed with a penetrating gaze.

Around the vast winged chair in which she is pontificating an entire petty court in grouped, of which she is the pivot; there are old aristocrats in ruffed coats powdered with Spanish tobacco; old women who, like her, regret the good old times; young ones who are waiting for some piquant tale of a gallant adventure of the Restoration; and, finally, men of various ages flattering her, some by virtue of confidence in her long experience, others by ambition, knowing that her influence is all-powerful with some minister or other. There are also some in that number, people of intelligence, who find a certain charm in listening to the words falling briefly and abruptly from the Marquise’s lips. What pleases them most about her is that the tone in which she retraces her memories is redolent with conviction—a rare thing today.

In November 1873, the petty court of the Hôtel de la Roche-Houdion had obtained the government’s consent to make an approach to the Comte de Chambord.4 His return being already certain, the senior functionaries of the future sovereign were designated in advance, and the Marquise was congratulating herself on the triumph of her dearest hopes when the question of the flag suddenly put an end to communication between Versailles and Frohsdorf. The Comte de Chambord refused to substitute the flag of the usurper for that of his family, and for that consideration alone, paltry in appearance but decisive in reality, preferred to retain a voluntary exile.

That news fell upon the Hôtel de la Roche-Houdion like a thunderbolt. All hope was henceforth lost. However, little by little, confidence returned as events transpired and a new conspiracy was organized by a small committee in the Marquise’s house, whose friends, with one exception, had adopted liberal ideas.

That opposition came from none other than Monsieur Landet, a senator, member of the Institut—the Académie des sciences morales et politiques—Officier de la Légion d’honneur, etc. A Federal Republican, he extolled the system of the United States and rejected with all the force of a tight dialectic the incessant attacks that the Marquise and her aides-de-camp launched at him. Why was Monsieur Landet, in spite of the stripe of his Republicanism, one of the Marquise’s Monday regulars? That was a mystery that we shall not even attempt to plumb. At any rate, a conversation without debate becomes monotonous; Monsieur Landet revived it with his savant controversy, and perhaps he had only been admitted to add a grain of salt to the charm of the meetings. Still, he was the wolf in that sheepfold, in which he had become the most exquisite guest.

A large head, framed by long, graying hair, with small green eyes as piercing as a drill, fleshy lips, strongly-chiseled features, the whole set on a thin body wrapped up in a black frock-coat buttoned up to the neck, only allowing the passage of the narrow border of a white cravat—that was the man, physically: one of those individuals withered by study to whom one almost does not dare to attribute a sex. Beneath that frail envelope, however, the multiple intelligence of a fine and satirical mind was hidden, with an astonishing profundity of insight. In the matter of opinions he never gave his own, for fear of having to retract it one day. If I said, just now, that he was a Federal Republican, it was because the elegance he deployed in all circumstances in bringing out the advantages of the government of the United States gave grounds for believing that he had a marked preference for that system.

He was one of those people who only make pronouncements with careful reservations and who finds the means to be something under every regime. He was a charming conversationalist, a distinguished economist, a witty and erudite writer and a refined man of the world.

From time to time, the Marquise looked at the clock, giving signs of impatience. She had announced a surprise.

The conversation was animated; people were talking about the politics of the day, current plays and new novels.

Monsieur Landet, closely surrounded, was playing with his listeners like a cat with a mouse. He was talking a great deal but saying nothing. It would have taken a fine mind to divine his secret thoughts.

Suddenly, over the general brouhaha, a domestic announced “Monsieur Hobson.”

As that name passed through the drawing-rooms, all eyes were turned to a man of about 40, tall and slim and as flexible as a reed. A thick forest of black curly hair darkened his head. Profoundly ensconced beneath his eyebrows, coal-black eyes as shiny as carbuncles, with a gaze of unsustainable fixity, illuminated his face. All of the extraordinary person’s life seemed to reside there.

A murmur of astonishment greeted his entrance. Who had not heard talk of the celebrated American magnetizer and spiritualist, Hobson? This, then, was the surprise that the Marquise had planned for her guests!

With the perfect ease of a man accustomed to being examined from head to toe, Hobson went straight to the Marquise.

“You have done me the honor of sending me an invitation, Madame,” he said, bowing deeply. “Here I am.”

“I was almost despairing of your response, my dear Monsieur Hobson,” the Marquise replied, indicating a chair beside her.

“I beg you to excuse me, Madame, if I am slightly late; I was retained this evening by a spirit.”

“By a spirit!”

The word ran through the assembly as if borne by an electric wire.

“By a spirit, Madame, yes—does that astonish you? It is by the intermediary of spirits that I am in daily communication with the other world.”

“With the other world! I confess that that surpasses the limits of my convictions.”

“I’m not talking about other planets; I mean the world of the dead. Spirits, detached from their bodies after death, wander in the sphere of terrestrial attraction, waiting to be given, by virtue of a new incarnation, a new enterprise in life, in a new body, appropriate to the demands of the epoch into which they will be reborn on Earth.”

“You seriously believe in metempsychosis, then?”

“Certainly, Madame. It is the basis of creation.”

“And from our world, you claim to be in correspondence with the dead?”

“Yes, Madame. Death is merely the transition from this life to another. The body finishes therewith, but the soul that has been that body’s spark during the trajectory of human existence, deprived of its carnal bonds, is purified in the atmosphere until the Supreme Being judges it appropriate to continue the proof of existences in a society relative to its improvement. During that intervening period, it is not completely isolated from beings who have been dear to it, or who are linked to it by blood, and the magnetic attachments that still chain it to the Earth permit it to remain in permanent communication with them.”

“So you see magnetism everywhere, then?”

“Everywher

e, as you say. Magnetism is the invisible agent that attracts and repels, which engenders sympathy and antipathy, the ultimate motive of all sentiments.”

“I’ll wager that you find it in love?” a joker put in.

“More than anywhere else,” Hobson replied. “Is not love, insofar as it is a sentiment, the most sudden, the most poignant and the most irresistible of all those that take possession of the soul; like any passion of the senses, is it not an unconscious attraction, to which we all submit, the great and the pretty alike, save for certain strong minds who make a game of defying nature, or when another passion—ambition, for example—absorbs it completely? ‘Love comes without one thinking about it; the mind goes to it of its own accord; nature wishes it, and issues the command.’5

“The Creator has formed, with a material and perishable substance, two essentially contrary beings, with the goal of bringing them together for generation, but he has animated both of them with the same immortal fire: the soul. The soul is a parcel of his divinity; it is the hyphen facilitating the joining together of a man and a woman.

“Why unite two different beings and make reproduction a linking of two components? Because in nature, everything follows an invariable law; in the same way that, in physics, a negative pole attracts a positive pole, in love, the woman attracts the man, and reciprocally.

“How can that immutable attraction of the man toward the woman and the woman toward the man be explained, if not by a sort of magnetic current, which we may call animal electricity? We all possess within us a certain dose of fluid emanated from the ethereal, invisible, impalpable substance that forms the soul. We transmit that fluid by the pressure of the hand, by the contact of the body, and above all by the force of the gaze, which is its most subtle and active agent. Hence the influence of a superior will upon an inferior one, a necessary consequence of love. It is in the order of things that one dominates the other, for, when that magnetic superiority no longer makes itself felt, love is gradually annihilated, to make weary for a sentiment of another kind: amity, which is the lot of old age. This transmission of fluids operates its cohesion by means of hooked atoms, according to the system of Descartes.

“Love does not always encounter reciprocity. It is often the case that only one of the two is subject to the fluidic influence, and that the other does not feel the effects of the magnetic transmission. That is because animal electricity, more developed in one than the other, is unable find a sufficient force of cohesion in the subject that it dominates because another current is drawing it in another direction—for in nature, all is proportionate, and a man and a woman are only truly united by love when the transmission operates on both parts with equal spontaneity, without the effort of thought. Unshared love is thus not true love; it wearies, softens and fails of its own accord.

“It is wrong to give the name of love to the violent sentiment that is born in the imagination and is merely the fruit of a temporary impression; that ought to be given the name of passion, for love and passion are totally different.

“Love derives from the soul; it is the impression produced on our soul by another soul. Passion derives from the senses; it is the impression produced on our senses by the attraction of a momentary charm. How little beauty counts for in true love! It is a more or less graceful frame, which strikes the eyes, but contributes nothing to the natural impulse that constitutes love. These two quite distinct sentiments should not, therefore, be confused, and the accessory should not be mistaken for the fundamental. Passion only lasts as long as caprice; love is eternal. One obeys the soul, the other the body.”

“But then,” the Marquise objected, “if this exchange of transmission is absolutely necessary to produce love, instinctively, without the effort of thought, many people risk not encountering their counterpart.”

“That is because people cannot wait,” Hobson continued. “If a man is wise enough to leave himself to his natural impressions, he will encounter the counterpart that is destined for him—but if he tries too hard to find it, in the course of that pursuit of the ideal, he excites his imagination, wearies his heart, falsifies his judgment and ends up realizing that the further he goes, the more he deceives himself. It is thus that one sees the dangerous game played by those who record in their journals as many love affairs are there are months in the year.

“To return to the role of magnetism in human organization, however, the man or woman who knows the influence of the will does not make use of it too often for a momentary caprice.

“Certain women, generally nervous by nature, emit such a quantity of fluid and enjoy such a subtlety of gaze that they inundate and transpierce the men who approach them with it, and inculcate an invincible passion in them, purely by virtue of that magnetic pressure. The existence of the sirens of antiquity, so long debated, becomes easy to understand. Their enchantments were merely the abuse of a fluidic force with which they enveloped the travelers attracted by the charm of their voices. But that sudden passion is extinguished as soon as the dazzled man is no longer in the power of the woman he thinks he loves, because the current to which he has fallen victim has not found a corresponding current in his soul—or, rather, because the currents that are exchanged emanate from a material substance.”

“You’re making love into a sort of fatal combination to which we are condemned by invariable laws,” said an old dowager, shocked by the magnetizer’s argument. She was English by birth.

“Yes, Madame; love is the principle of generation. We are all subject to it. It is, therefore, logical that the atoms of souls are interlinked according to the law of sympathy, or repel one another, following the contrary law.”

“So, to you, everything in this world is magnetism,” said a writer, who was following Hobson’s reasoning attentively.

“Everything,” the latter replied, “in material beings as in simple substances. Water advances and recoils under the influence of lunar rays; that is flux and reflux. A stone, detached from the summit of a mountain and rolling down its side, obeys the force that tends to draw it toward the center of the Earth. A tourist who climbs a steep slope is seized by vertigo at the sight of the gaping precipice at his feet, an irresistible impulse pulling him into the depths of the gulf; it is the magnetic force that is attracting him, like the stone to the center of the Earth. The meeting of two currents in the atmosphere produces a detonation: a lightning-bolt; again, it is the magnetic fluid, which here takes the name of electricity.”

“All that is purely and simply physics,” Monsieur Landet interjected in his turn. “The magnetic effects of which you speak are those which experience demonstrates to us—but I don’t believe that the soul is subject to the same principle. A body, of whatever sort, by virtue of the material elements that comprise it, gives off a sort of atmosphere endowed with magnetic properties, exercising on another body the influence of a superior or inferior force. That is what causes the terrestrial nucleus, swollen by the molecules aggregated around it, to attract as if to a common center, by virtue of the Earth’s rotation, the bodies that are within its radius of attraction. But that such a power, emanating from a simple substance, obtains identical effects on a substance of the same sort I cannot conceive. Common sense refuses to admit the attractive and repulsive force of something impalpable and invisible. To obtain a physical force requires a body constituted of material molecules.”

“You’re speaking as a philosopher, Monsieur,” Hobson retorted. “Personally, I’m speaking as a practitioner convinced by long experience. Philosophy is all very well, but it is sometimes found wanting. When you have heard me out, and especially when you have seen me at work, perhaps you will consent to alloy magnetism with psychology—I might even say with metaphysics.”

“With metaphysics! That’s deifying matter.”

“Would you care to do me the honor of witnessing an experiment? Better than that—would you care to be the subject of one?”

“Do you intend to put me to sleep?”

“Why

not?”

“Oh! I’ll wager that you’ll never manage it.”

“Who knows?”

“You’re serious, then?”

“Very serious. You’ve proposed a wager—I accept it. What is the stake?”

“Well! You’re American to the tips of your fingernails. It will be, if you wish, a lunch at the Café Anglais.”

“Agreed.”

“When is the séance?”

“Today.”

“Today? Where?”

“Here.”

“In this drawing-room? You don’t mean it.”

“The wager was made in public; it’s necessary that the experiment likewise be in public.”

“So be it!”

A frisson ran through the drawing-rooms, and the guests, enticed by that strange wager, flowed into the principal room. Conversations stopped, gazes fixing upon the magnetizer and the savant.

“Install yourself comfortably in this armchair, as if you were about to undertake a long railway journey,” said Hobson. “The rest is up to me.”

Monsieur Landet sank into a vast wing-backed chair and waited.

Hobson retreated to the far side of the room and, after a few minutes of meditation, to isolate his thoughts, he folded his arms across his chest and raised his eyes, which he darted at the savant with a grim fixity.

He was no longer the same man. His long, thin body was animated by a superhuman force. His nerves, taut with the effort of his will, curled his bony fingers. His body was agitated by a febrile tremor. The muscles of his face contracted, his shining eyes projecting an unsustainable glare, like that of an electric fire. They had phosphorescent gleams, and caused all gazes within the range of their radiation to be lowered. They plunged upon Monsieur Landet and pinned him to his armchair.

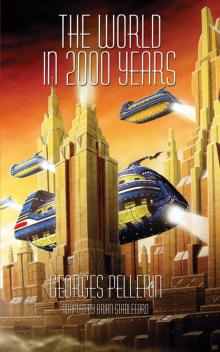

The World in 2000 Years

The World in 2000 Years